It is a sign of the troubled times we live in that what we add to the Lexicon is terms like ‘post-fact’ and ‘post-truth’. My submission: This is yet another indicator that the dominant narrative, that is the narrative which could be described as the ‘mainstream narrative’ is a manufactured one; that it is carefully calibrated and nurtured.

Many years ago, when I was a student at Delhi University, I recall reading a fascinating book, ‘What is History?’ by E.H. Carr. Carr was not even a historian. He was an analyst in Foreign Office. Addressing the issue, he demonstrated that a historian has to give shape to facts. The fact that Ceasar crossed a stream called the Rubicon is certainly a fact. If you add that millions of people crossed the Rubicon prior to Ceasor and several million crossed the Rubicon after him, the ‘fact’ gets submerged in the ‘perspective’. In short, the historian or the commentator provides shape, life and interpretation to facts. Up to that point, as a student, I am comfortable. But the new terms ‘post-truth’, ‘post-fact’ begin to enter dangerous territory because they involve, at the very least, an embellishment of facts. It doesn’t stop there. President Trump’s adviser Kellyanne Conway went several steps further in defending the White House spokesperson when she referred to ‘alternate facts’. This enters dangerous territory and will invite the charge of ‘inventing’ facts.

Let us briefly look at the Western Liberal Democratic Order. Let us start with the genesis of the term. In the summer of 1989, Francis Fukuyama’s influential and much celebrated book, “The End of History and the Last Man” announced the triumph of liberal democracy and the arrival of a post-ideological world. “What we are witnessing”, he wrote and I quote, “is not just the end of the Cold War, or a passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such; that is, the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalisation of western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.

” When he wrote the book, Fukuyama was a researcher for the Rand Corporation – this is before he joined the State Department. I was reminded about Fukuyama’s sleight of hand when I read a piece by Eliane Glaser a few years ago in the Guardian and this takes the cake. And this was in 1989.

“… the class issue has actually been successfully resolved in the West… the egalitarianism of modern America represents the essential achievement of the classless society envisaged by Marx.”(Glaser quoting Fukuyama in 2014)

Wow!

The ‘End of the History and the Last Man’, or rather the writing of it, it bears recall – time and context wise – represents the dominant narrative of that day: globalization, Washington consensus, trade liberalization, human rights, interventionist mindsets, where, including if necessary through regime change. With philosophers and thinkers like these, who needs enemies?

This was, with the benefit of hindsight, a systemic and powerful generation of fault lines. Capitalism pretends to love free markets. In reality, it rigs markets for elites.

Again, an attempt was made to falsify the narrative.

There is overwhelming evidence that trade has contributed to global prosperity, raised standards of living and contributed to steadily growing real income. Globalization, however, produces both winners and losers. Trade produces not only prosperity but also inequalities. It can have a devastating effect on the manufacturing sector if it is subjected to subsidized or dumped products and exchange rate manipulation. Although the trading system provides remedies against unfair trading practices – little can be done if predatory pricing is institutionally entrenched where entire systems do not work on the basis of market prices and it is difficult to determine where state subsidization ends and enterprise dumping begins.

I have absolutely no doubt that Brexit and the Trump victory are the outcomes, at one level, of the industrialized western democracies not having learnt to cope and manage to live with the low rates of economic growth.

The anti-trade and anti-globalization rhetoric in the presidential campaign echoed arguments in the Brexit debate. Even if the ‘Remain’ vote had won, half of the British electorate clearly would have felt alienated. The financial crisis of 2008 and its aftermath of slow growth in developed economies intensified inequalities in the sharing of gains and losses, exacerbating inequalities and national level divisions between the better educated and economically well-off and the rest of the population.

Both the Brexit vote and the Trump victory represent at another level, the triumph of the alienated voter. But the most affected segments of society were provided leadership by the left of the centre and liberal intellectuals, particularly those who had been nurtured by the Liberal Democratic Order. Something similar had happened in India in May 2014.

Delivering the third Nikhil Chakravarty Memorial Lecture on October 26, 2014, Romila Thapar described the public intellectual in India as an endangered species. The lecture titled, ‘To Question or Not to Question? That is the Question’, was revised, expanded and published by Aleph in association with the Book Review Literary Trust in 2015.

Nikhil Chakravarty thought and wrote about contemporary problems, flawlessly performing the role expected of public intellectuals asking questions of those who took decisions that impinged the society. ‘NC’ guarded his independence fiercely. He shunned membership of the Communist Party of India for its collaborationist stance during the Emergency and justified declining the Padma Bhushan by explaining it would curtail his independence as a journalist. Being well read themselves, the doers of NC’s generation respected intellectual and academic opinion about public matters. The space for such discussion today, it is now being argued, has shrunk and the intellectual parameters narrowed. Is this really the case? In fairness to Romila Thapar, she claims this is a process that has been in the making for over six decades.

Many an incumbent politician, according to this view, is characterized by little, if any, vision of the model of society they wish to construct barring those that incline towards extreme nationalism and their ambition of creating an enclosed, uncritical, inward-looking society. For many, the aspiration is merely to make money and push people around in the process. Possibly, in this ambience, India’s public intellectuals shy away from debating the quality of the interconnection. Romila Thapar and her co-authors repeatedly echo the argument in The Public Intellectual in India.

Such characterizations, at first glance, appear attractive, but subjected to closer scrutiny, the faint lies begin to appear. Several questions suggest themselves: Is the public intellectual ideology neutral? Is it in order for the public intellectual to allow his/her intellectual intent to be put to narrow and partisan uses by political parties? The responses to these questions need to be considered carefully. The choice of words employed will be indicative of intellectual bias and leanings on the ideological spectrum.

Witness the following today – and this is extracted from The Public Intellectual in India– even the mantra of ‘development’ sounds hollow, since thus far, it has seemed to be a mirage. The mafia, no longer outside the system, remains entrenched within it. Religion and politics are now seemingly more intertwined, although more often than not, the root-cause for disruptive behavior is not hurt religious sentiments, as is claimed, but the bid to assert power and control over some crucial section of civil society. The present political scene, thus, seems to be regarded as a now-or-never situation by those that would want the Hindu Right to impose their will on Indian society.

Delivered less than six months after the installation of the Modi Government, the lecture and the subsequent volume would have us believe that the version of majoritarian fundamentalism being propagated these days is most conducive to aggressive mobilization; that Hindutva, by definition, is not identical to Hinduism; and whereas the latter is an ancient religion, the former, only a young ideology engineered for political mobilization. The critical discourse on this divergence is amply rich. However, is merely asking questions sufficient or should a debate also be accompanied by facets of advocacy?

As a proud member of the BJP, I gladly accept and celebrate the right to dissent and criticism from public intellectuals. I often ask myself basic questions: Who is an intellectual? Does possession of some intellect alone so qualify a person? Who and what determines the conferral of the title, “public intellectual”?

Criticism needs, at the very least, to anchor itself in an empirically verifiable base. For most of the seventy years of India’s existence as an independent country, the Congress Party provided a comfortable nurturing environment for liberal and leftwing intellectuals. In my own small, limited world, a public intellectual does not need to be defined. The honorific is earned on the basis of decades of dedication to professional academic excellence, fearless and robust advocacy of what serves societal interests, public good and equally robust articulation of dissent. Each one of us can have our own shortlist of who qualifies for inclusion as an intellectual.

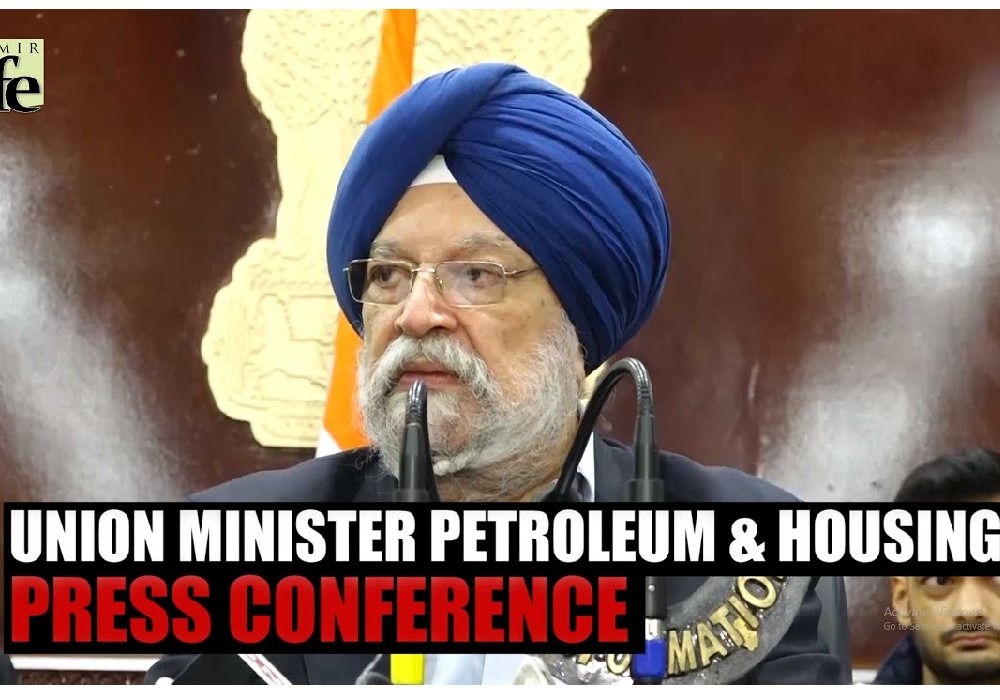

Synopsis Union Minister Hardeep Singh Puri stated India's commitment to an inclusive global energy future through open collaboration, highlighting the India-Middle ..

देश में एक करोड़ यात्री प्रतिदिन कर रहे हैं मेट्रो की सवारी: पुरी ..

Union Minister for Petroleum and Natural Gas and Housing and Urban Affairs, Hardeep Singh Puri addressing a press conference in ..

Joint Press Conference by Shri Hardeep Singh Puri & Dr Sudhanshu Trivedi at BJP HQ| LIVE | ISM MEDIA ..

(3).jpg)

"I wish a speedy recovery to former Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh Ji. God grant him good health," Puri wrote. ..