Is the UN at 70 fit for purpose?

Some Reflections

5 December 2015

The seventieth anniversary is an important milestone in the life of any organization. The coming months will also see the election of the ninth Secretary General of the United Nations. 2016 will also be election year in the United States.

The UN Charter, signed on June 26 1945 at San Francisco’s Opera House, echoed America’s Constitution, while rhapsodizing about the future.

“We the peoples of the United Nations,” the nations proclaimed, determined “to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war… to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights… to establish conditions under which justice and respect for the obligations arising from treaties and other sources of international law can be maintained, and to promote social progress and better stands of life in larger freedom…”

The decades that followed witnessed the popularity of the UN plummet and enthusiasm for multilateral approaches to global challenges vary from lukewarm to outright hostility. The ‘UN’ collectively was not always responsible for the strain in relations between itself and its member states.

There are three UNs out there, one, the 193 member states, two, the Secretariat and the third UN, civil society, NGOs, think tanks and a vast array of organizations, including possibly the private sector, that now are intimately involved with the work of the United Nations.

The world of 2015 and the world of 1945 are, to say the least, vastly different. So are the challenges that the international community faces today. The design and architecture of the UN, its structure and vision, as contained in the Charter, embodied the hopes and aspirations of the international community whilst the Second World War was still raging.

The 850 delegates who met in San Francisco to establish the UN on 25 April 1945 did so five days before Adolf Hitler killed himself. They came from 50 nations representing close to 80 percent of the world’s population. This was one of the few happy outcomes of World War II.

The genesis of the UN can in fact be traced back to 1941, the seeds of which were sown in the crucible of the Second World War. By 1941, much of Europe and Asia Pacific region had fallen to the Axis powers led by Germany, Italy and Japan. The opposing Allied Powers, however, were already aiming at more than military victory; they were planning how they might achieve lasting peace and prosperity after the war.

Developments took place quickly thereafter. The Atlantic Charter, the Declaration by United Nations, the Moscow and Tehran Conferences, the Dumbarton Oaks Conversations, the Yalta Conference, Potsdam and finally the San Francisco Conference.

I mention the above sequential evolving steps only to try to drive home the point that it was the Second World War that generated the traction and energy that led to the establishment of the United Nations, as we know it today. Indeed, absent the annihilation of the War, the momentum for its establishment may have been lacking. This has led cynics also to regrettably observe that absent another major war, basic reform of the United Nations may be difficult to achieve.

For decades, the absence of another major war was mentioned as the single most important contribution of the United Nations to the maintenance of international peace and security. Cynics did and even now continue to argue that it was not the UN but the deterrence provided by nuclear weapons that was responsible for averting another major war.

Having spent a considerable part of a professional career spanning four decades working the multilateral system and having had the privilege of representing India on the Security Council, I find it difficult to subscribe to simplistic assessments of the UN’s achievements on the peace and security front.

The 2003 military action in Iraq, without the Council’s authorization for the ‘use of force’, the manner in which the 2011 authorization for the ‘use of force’ was undertaken in Libya following Resolution 1973 and the inaction and total helplessness of the United Nations in relation to the carnage in Syria raise disturbing questions, apart from constituting a severe indictment of the United Nations in general and the Security Council, in particular.

Emerging global challenges require, at the very least, continuing readjustments to the way the Charter is applied to contemporary issues of security and development.

The nature of armed conflict itself has changed. Since 1945, the first generation of conflicts was more conducive to the UN’s involvement. It was a traditional paradigm: a peace agreement following a conflict, a ceasefire with subsequent blue helmet deployment to keep the peace.

The complex nature of conflicts today is characterized by a series of asymmetric threats: from the rise of the armed non-state military actor to the growth of ideologically-driven groups. Warfare is modernized – indeed hybridized –and threats often intersect in ways which make them difficult to respond to, for example, the relationship between terrorism and organized crime.

The Charter established a structure anchored in a post Westpahlian state centric model drawing inspiration from “We the peoples”. The reconciling of the two played and continues to play on the latent tension between the two. And for good reason. The defining feature of the multilateral order – “the state” – has come under unprecedented stress. From Europe to the Middle East, Africa, and the Americas, rising numbers have taken to the streets to protest inequality and ineffective/illegitimate governance, threatening the very notion of a social contract. An empowered middle class means more demands on government and less acceptance of politics as usual. The implications of a breakdown in state-society relations on the multilateral system are severe: if the “state” as a notion loses currency, the notion of an “inter-state” system as a whole cannot but be called into question.

Migration and refugee flows have presented a new demographic threat. There will be 405 million migrants by 2050. If unchecked, this ongoing trend, including economic and climate migrations, will have huge implications on social cohesion of host countries.

Nearly 1.2 billion people, including a third of the world’s poor, continue to languish in “fragile states” that typify paralyzed institutions and meager incomes. Over half the world’s ongoing conflicts are concentrated to these struggling states. Worse, even urbanization in the world’s fragile pockets has been riddled with developmental and demographic hurdles, leading to the mushrooming of “fragile cities” with their own set of woes, ranging from trafficking to mafia-wars. These vulnerable cities and states are in no position to achieve their quota of MDGs any time soon, despite attracting multilateral aid.’

Humanitarian disasters add a layer of complexity to this dynamic. The humanitarian catastrophe emanating out of Syria—with over 4 million refugees—places immense pressures on the bordering countries of Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, and Iraq, which are on the cusp of a tipping point, as well as beyond to Europe.

By 2030 the world will need at least 30 percent more water, 50 percent more food and 45 percent more energy. Climate will likely result in greater competition for shrinking water supplies, increasing the potential for new resource wars over water as opposed to energy or minerals. Failure of governments to address the negative effects of climate change, food insecurity, and pandemics are likely to drive disillusionment at national, regional, and global governance structures.

The inter-connectedness of economies and societies means that the risks are more contagious and crises reverberate across issues and borders, whether they relate for example to health, refugees, violence or—more often—all three at the same time.

Unless all countries big and small alike can set aside their immediate short-term differences and rededicate themselves to the principles enshrined in the UN Charter– prevention rather than intervention – the situation can only worsen. The deep longing for peace was the basis for the creation of the United Nations. It is only that same yearning for peace, stability and growth which can provide to the United Nations hope for survival.

Reflecting on this topic four years ago while serving on the Security Council as India’s Permanent Representative, I expressed hesitation about how relevant the UN was then and how relevant it will be in 2025. I am still not entirely sure about its relevance. Beyond those of us who are involved in the industry that surrounds the work of the UN. The market place’s perception of us is quite different.

In an increasingly crowded multilateral arena – the G20, NATO, the African Union, to name but a few – the shots continue to be called elsewhere. Meanwhile the United Nations –the quintessential organization of states and alleged heart of the multilateral system– is close to “dying the death of a thousand cuts”. Indeed, we will perhaps not wake up one morning to hear that the UN has ceased to exist. But we are on the cusp of witnessing it fade into the background as its credibility erodes, incrementally. It is strange and surreal, dare I say dangerous, to think that the UN is evolving into nothing other than the world’s largest NGO.

Future reform was foreshadowed during the Act of Creation itself and is embodied in the wise words of President Truman in 1945:

“This Charter … will be expanded and improved as time goes on. No one claims that it is now a final or a perfect instrument. It has not been poured into any fixed mold. Changing world conditions will require readjustments—but they will be the readjustments of peace and not of war.”

As Secretary General of the Independent Commission on Multilateralism (ICM), an independent review of the multilateral system anchored in the United Nations, I see the ICM as one small part of this continuing process of reform. The ICM is drawn essentially from the “third” UN (civil society) but with a crucial difference. We are basing our assessment on the functioning of the system in close collaboration with the first two UNs.

The mandate and intention is not to produce an arm’s length review of the system designed to produce a 21st century utopia but a more practical exercise. The ICM seeks to provide the international community with a range of options on how the UN best remains “fit for purpose” against the new challenges confronting the system. This two year long exercise will examine the functioning of the UN from a functional rather than an institutional matrix through 16 identified thematic areas. These are listed on the screen.

To suggest that the UN has remained static since 1945 would be absurd. The institution has been in a continuing process of evolution, including: a limited expansion of the Security Council in 1965; the establishment of a range of UN specialized agencies including the IAEA; and most recently the establishment of the International Criminal Court, the Peace Building Commission, the Human Rights Council and UN Women.

As for the functional aspects of the UN’s operations, the Secretary General convened a review of the mandate for peace operations through a recently constituted High-Level Independent Panel on Peace Operations, headed by José Ramos-Horta (who is also one of the co-chairs of the ICM). Another key aspect of functional progress is signaled by the recently adopted and ambitious 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda. This process has the potential to alter the future course of development for the coming decades.

While these steps reflect gradual progress in overall UN reform, a long-standing and complex subject that has been deadlocked for the last three decades is the core question of Security Council reform. When the United Nations was created in 1945, it comprised 51 member states. Today its membership has increased nearly fourfold to 193. While the Security Council membership was increased from 11 to 15 in the non-permanent category in 1965, it continues to make critical decisions on behalf of the other 193 members.

One of the responsibilities of the ICM will be to consult widely across the UN membership to bring forward a consolidated menu of options for possible reform – not only to provide support for the overall reform agenda, but also to focus the debate among member states on the core alternatives for change.

Among its greatest recognized strengths is the UN’s convening power. Multilateralism is more than a venue: it is a strategy and set of principles for cooperative problem solving amongst independent states, each of which claims sovereign equality, and each of which is affected by problems it cannot solve alone.

The ultimate failure of the UN however represents a collective failure of the member states, the “first UN”. It is precisely the central constituents – its 193 Member States –which have rendered the system increasingly contested, underutilized, and thus with decreasing capacity to deal with the emerging threats. Such a trend is epitomized by the breakdown of consensus and decision-making at the Security Council, which has invited criticism when, as I mentioned previsouly it authorized the use of force in Libya in 2011 and when consensus could not be achieved on Syria and Ukraine subsequently, resulting in inaction.

The impunity with which member states are violating the most basic tenets of international law, without being held accountable, reflects dismally on the current state of play. Key powers are ultimately not wedded to the notion of global governance that would limit their authority.

Given the global security environment, there is a case to be made that multilateralism is needed now more than ever. The strong are sometimes tempted to act unilaterally, but as history has shown, they have not been unaware of the advantages of operating within multilateral systems. For the small and less powerful, multilateralism represents an insurance policy and a preferred framework within which they can work on building issue-based coalitions. Multilateral approaches carry more legitimacy, more efficient resource allocation, and generally come with a cheaper price tag.

As the world’s largest and most vibrant parliamentary democracy, India has a role to play as a trendsetter in this troubled multilateral environment. As an advocate of inclusiveness – rather than exceptionalism – it has many good values to project. Moreover, India’s faith in the United Nations is rooted in our ancient belief of the world as one family – Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam – and the sense of responsibility that comes with representing one-sixth of humanity.

But we – as India – must also accept that the challenges are global. We are all in this together. There is a real need for multilateralism and we cannot underestimate the need.

The key concepts that will likely be key pillars of our report: Prevention, implementation, inclusivity, partnerships and new technologies.

As the ICM pursues its brainstorming and formulates its recommendations, it appears clear that what we produce must be anchored in pragmatism and couched in modesty.

It cannot be too minor lest it be subsumed by the status quo. But it cannot be a radical/drastic overhaul either lest it completely alienate certain key states those whose buy-in is crucial. It is an approach that needs to be incremental but not at the pace of the tortoise. I would be happy to spell out our approach in greater detail, should you so wish.

Thank you

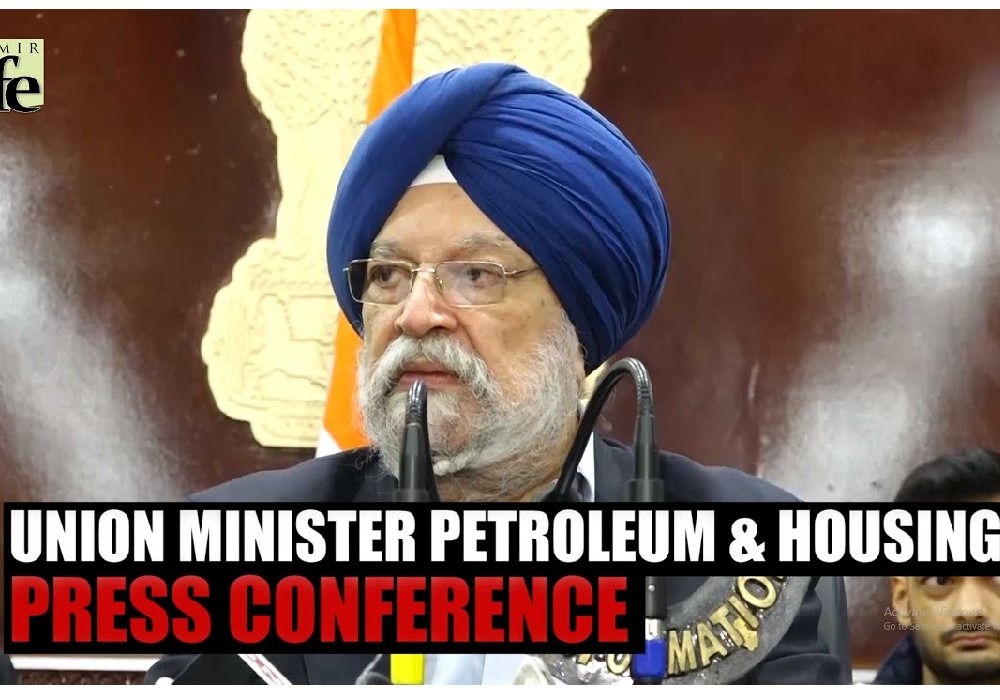

Synopsis Union Minister Hardeep Singh Puri stated India's commitment to an inclusive global energy future through open collaboration, highlighting the India-Middle ..

देश में एक करोड़ यात्री प्रतिदिन कर रहे हैं मेट्रो की सवारी: पुरी ..

Union Minister for Petroleum and Natural Gas and Housing and Urban Affairs, Hardeep Singh Puri addressing a press conference in ..

Joint Press Conference by Shri Hardeep Singh Puri & Dr Sudhanshu Trivedi at BJP HQ| LIVE | ISM MEDIA ..

(3).jpg)

"I wish a speedy recovery to former Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh Ji. God grant him good health," Puri wrote. ..