Text of my talk on the UN at Society for Policy Studies on 7 December 2015 I would like to thank the Society for Policy Studies (SPS) for this invitation. It is a great privilege to address this distinguished gathering and that too at a venue associated with three of the professionally most satisfying years of my long career.

The Charter of the United Nations came into force on October 24, 1945. India was among its founding members. The deep longing for peace, was t he basis for the creation of the United Nations.

Speaking at another venue two days ago, on 5 December 2015, I focused on whether the United Nations is fit for purpose as it celebrates its 70th anniversary and it is facing unprecedented challenges. Policy-induced failures, action with or without authorization for ‘use of force’ have resulted in the unraveling of countries, with long-term ramifications for the global community: from the highest numbers of displaced peoples since World War II to global pandemics. Today, violent non-state actors, epitomized by Daesh, are in control of territory as large as the United Kingdom.

Multilateral organizations are struggling to adapt to the breadth and pace of the multiple and multi layered crises. The drafters of the UN Charter could, in all fairness, not have anticipated many of the challenges of today’s world. The UN is being tested as never before.

These crises have provoked soul-searching within the organization. The UN launched three important reviews in the past two years. These look at its peace operations, peace-building architecture and issues related to women peace and security. The three reviews concluded with a broadly converging recommendation: the current structure of the UN is not entirely fit for its intended purposes nor is it able to fully address the challenges of the 21st Century.

In additions to the reviews mentioned, on September 25, 2015, 193 member states adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The 2030 Agenda titled, with no hesitation or lack of modesty, as “transforming the world” will prove to be a tall order for most, if not all countries.

It is the most ambitious development plan that the UN and member states have ever adopted. This new framework includes a set of 17 sustainable development goals that range from poverty eradication to reducing inequality, promoting peaceful and inclusive societies and addressing climate change.

The question that immediately comes to mind is whether we, States, civil society and international organizations – are prepared to address the daunting scale, complexity and ambition of the new Agenda?

The 2030 Agenda calls for a new mindset. It envisions five paradigm shifts that some would call: “leaps of faith.” Should these be achieved, the UN would be coming-of-age in the 21st Century. The five transformative shifts in the 2030 Agenda are:

(1) Universal application;

(2) Systemic integration;

(3) Include peace as indispensable for its success;

(4) Bind sustainable development and climate change; and

(5)Transcend the silos to achieve gender equality and women’s empowerment

(1) Its universal application: Implementation is expected in all countries- this is a very big leap. Previously, developed countries had the role of being donors. They were considered the model of progress. The tables have turned and now the north is also required to implement, measure and report on the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. If the developed world wants to participate sincerely in this new framework, it has to change its national policies on many fronts, including on: migration, inequality, climate change and unsustainable patterns of consumption and production.

(2) The 2030 Agenda calls for systemic integration: the United Nations has comfortably operated in silos for the last 70 years. The Charter and the structures of the UN revolve around pillars, this in part explains the fragmentation and silos that exist today. The UN Charter deliberately separated the management of international peace and security, entrusted to the Security Council, from the management of development and human rights, entrusted to the Economic and Social Council and the General Assembly.

During the cold war years, it was this division that made it acceptable for countries with profound political differences to pursue cooperation in the economic and social spheres. The governance structure of the United Nations remains stuck with an institutional framework designed for the past century that is now called upon to address the challenges of the 21stCentury. In order to fully achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, profound systemic issues of governance need to be addressed, including Security Council reform and revitalization of the General Assembly.

(3) Peace is a core element and condition for the overall success of the 2030 Agenda: The link between development and peace is not new. Boutros Boutros-Ghali’s 1992 “Agenda for Peace” had already proclaimed that there can be no peace without development and, conversely, that there can be no development without peace. The 2030 Agenda goes a step further by including a stand-alone goal (Goal 16) on “peaceful and inclusive societies” as an operational component, and not simply as rhetoric.

Targets under Goal 16 such as “reducing all forms of violence and related deaths” and “substantially reducing corruption and bribery,” are to be monitored and reported. Issues of governance that used to remain outside public and international scrutiny now form part of the development framework.

(4) The 2030 Agenda binds sustainable development and climate change in one track: Since 1992, sustainable development and climate change have been thought of as separate, often competing tracks. The development track has focused on eradicating poverty while climate change has centered on reducing emissions. However, recent studies show that climate change impacts could draw upto 720 million people back into extreme poverty. Without ambitious climate change actions, the 2030 Agenda could become an unattainable illusion.

The 2030 Agenda is the thread that connects efforts to eradicate poverty and at the same time tackle climate change. Already, 90% of all national climate change plans submitted to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) include adaptation as part of their response. Countries are now integrating climate in their national development policies. India announced its climate plan on October 2, 2015.

(5) The 2030 Agenda promotes the achievement of gender equality and women’s empowerment in all fields: 15 years ago the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 1325 on “Women and Peace and Security.” This watershed text placed women’s security high on its list of priorities. The seven subsequent resolutions in the intervening years continued to raise awareness on this issue. The creation of UN Women, a major UN reform in 2010 added further momentum to this process.

The 2030 Agenda includes a stand-alone goal on gender equality and empowerment of women and girls. SDG 5 has the potential to strengthen cooperation to implement Resolution 1325. It also provides a holistic view of the multiple roles women have in all fields of life, including in the economic, political and social dimensions, which have been often overlooked.

Now, what does the 2030 Agenda mean for India?

The newly adopted 2030 Agenda, in many ways, embodies a concept that resonates well in India, in terms of our civilizational ethos of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam– the whole world is our family. This new agenda is a unifying vision for humanity.

India has welcomed the 2030 Agenda, the core objective of which is to eradicate poverty in all its forms. Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressed the United Nations during the United Nations Development Summit and recognized that, “India’s development is mirrored in the Sustainable Development Goals.” The 2030 Agenda can help us achieve a goal we hold dear since independence: to eradicate poverty.

India was a constructive player during the negotiations of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This was an inclusive process that spanned over two years. We placed many national priorities at the core of this new global project. To name a few: economic growth, industrialization, infrastructure, and access to energy.

A daunting challenge we face is to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels and enhance our renewable energy sector. As the fourth largest emitter in the world, India must step-up. Our climate change plan submitted to the UNFCCC, envisions that we will produce 40% of our electricity from non-fossil fuel sources by 2030. This is a step in the right direction.

Currently, delegations are in the midst of negotiating a new climate agreement in Paris. The expectations of an ambitious climate agreement are low. All countries need to rise to the occasion and decide on a long-term goal to prevent the worst climate change scenarios predicted by scientists and limit the average global temperature rise to below two degrees Celsius.

Developed countries need to assume with all seriousness their historic responsibility on this issue. The Paris conference needs to deliver a strong climate finance package, including a credible path to meeting the $100 billion per year commitment by 2020. Developing countries also need to step up and address climate change in all sectors of society, particularly on energy.

Climate change requires a deeper level of multilateral cooperation. In this case, the real “enemy” cannot be subdued by sending “boots” to the frontline but rather by changing habits of unsustainable consumption and production.

India represents one-sixth of the world’s population. If we commit to implement the 2030 agenda and do our part to tackle climate change, the whole world stands to benefit. Future generations depend on our actions today.

As Secretary General of the Independent Commission on Multilateralism (ICM), an independent review of the multilateral system anchored in the United Nations, I see the ICM as one small part of this continuing process of reform.

As the ICM pursues its brainstorming and formulates its recommendations, it appears clear that what we produce must be anchored in pragmatism and couched in modesty.

The key concepts that will likely be key pillars of our report: Prevention, implementation, inclusivity, partnerships and new technologies.

Across all policy domains, the absolute centrality of prevention must be upheld. With regards to armed conflict, the answer lies in the Charter. This means reverting to the toolbox contained in Chapter VI, Article 33 including the need to seek solutions through negotiation, mediation and conciliation.This has largely been bypassed, with consequences for subsequent military actions, within the UNSC or amongst ad hoc coalitions.

The same conceptual framework of “prevention” applies across practically all of the policy domains of which the United Nations now work:

We have unfortunately grown accustomed to the notion of managing crises rather than solving the underlying problems. The Middle East is the example of this par excellence.

The Syrian conflict has entered its fourth year, with more than 300,000 killed, millions displaced and over 12 million in need of humanitarian assistance. The unraveling of Libya has produced a “Somalistan” on the Mediterranean coast. The ISIS/Daesh, the most vicious terror entity known to mankind, is holding territory larger than the United Kingdom and attracting recruits from over 100 countries, including many from rich Western economies. Yet these and other crises are barely managed, let alone solved. In Syria, the two countries which drew artificial lines in the sand are now the pen holders within the Security Council. With Daesh, we are once again trying to bomb an ideology: an unachievable task at the best of times. The right diagnosis, however, would highlight that the threat is coming from people who have a deep sense of alienation from the current order – of being excluded – whose sense of “participation” manifests itself in seeking redemption through these physical acts of violence. Once again, prevention is the key word. Prevention means getting at the underlying causation, not its symptoms.

One caveat to raise, however, is that long term preventive peace building requires a budget. There is no money for prevention in the UN today. On the other hand, recent crises in Libya, Syria, Yemen and Africa have shown the even higher costs to the UN and member states when conflicts are not resolved, and the results wash across many borders. When we fail to prevent, the cost is massive literally and figuratively. Prevention is cheaper than cure. The cost of measures to promote dialogue and peaceful mediation in a country in order to prevent conflict is, on average, just 10 per cent of the cost of recovery after a civil war.

The universal importance of a culture and practice of implementation of the decisions taken by member states and an effective system of performance auditing of this implementation should be a top priority.

There is widespread recognition that the UN system has produced an incredibly multifaceted framework of norms since 1945. The UN Charter, international law, and widespread normative mechanisms are broadly supported by member states and civil society. Dramatically less successful, however, is the implementation of those norms. Promotion of wider and more robust implementation of UN norms is thus both a challenge and an opportunity. Getting implementation “right” for the historic 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Agenda, for example, presents an excellent starting point.

Much needs to be done to address tension inherent between the “we the peoples” side of the Charter the established state centric model.

The UN must continue support citizen-oriented action in the face of the complex, interconnected, and fast evolving transnational problems. Participatory governance is the future.

A more “people-centered” approach from below will undoubtedly enhance the legitimacy of the system(s). A central component of this multilateral message is that governance at the national level is not just “state business”, but a partnership between the government and the people. Effective and legitimate governance can be best guaranteed if there is a central universal feedback system that allows all members of the community to give inputs and therefore feel like they are influential “governance” actors.

A more concerted effort should be made to recognize non-state actors as potential partners for peace. Innovative means of engagement represent a potential for peace-building, conciliation, and healthier state-society relations, and ultimately, more stable inter-state relations. This can only be guaranteed through further empowerment of women, engagement of youth and full participation of minority groups.

Much can be gained by bolstering existing partnerships and forging new ones across the multilateral order.

To revitalize its role at the center of multilateral governance, the United Nations must strengthen is capacity to engage with local and international partners. While the UN remains the best placed and most legitimate vehicle for international action, an emphasis on greater cooperation with regional and sub-regional organizations, civil society actors, and the private sector, would help bolster its standing as an effective leader in setting norms, coordinating responses, delivering services, and providing assistance when necessary. While the UN does not have to “be” everywhere, it still needs to be able to rely on functional partnerships and a holistically sound protocol for approaches on regional governance, in conjunction with the national and local level.

The overall approach of the Independent Commission on Multilateralism is that the principle of subsidiarity should apply, whereby solutions to problems should be delivered by the institution closest to the level where that problem is manifest: from national governments, to regional organizations and only to the UN where these two lower levels of recourse have been exhausted.

The role of new technologies should be better understood and utilized by the multilateral system. The intersection between technology and better governance can be better leveraged. Much has yet to be expanded on: from open government data, to the use of mobiles for government service delivery, to citizen reporting on government abuses.

The multilateral system will be at an advantage by investing in providing assistance on how new technologies can enhance governance processes. There is a need for an interdisciplinary critical analysis – quantitative, narrative, economic, historical, anthropological, political, and more — to make sense of how new technology impacts transparency and accountability. New technologies are an effective tool in our fight against poverty and an effective catalyst for development.

India has good examples to offer on this front. The way we have been using “Digital India” to improve targeting of benefits to the needy, make the delivery of services more efficient, catalyze development and increase citizen participation in governance is a case study for the world at large.

Conclusion

In his address to the General Assembly this year, Prime Minister Modi chose to quote the Mahatma: “One must care about the world one will not see”. I cannot think of a better dictum to guide us through this period of reform, revitalization and renewal.

The 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda, the Paris Climate Conference and the Independent Commission on Multilateralism, to name a few, are forward-looking exercises. They serve as an important reminder that, only through long-term planning, commitment and perseverance can we guarantee a safe and sustainable world for generations to come.

In today’s world, where agents of chaos continue to challenge the forces of order, the threat of bleakness should not to be taken lightly. The frontal challenge to civilizational values that we are witnessing today can only be dealt with collectively through a reinvigorated multilateralism.

To quote another great Indian statesman, “the first thing to remember and to strive for is to avoid a situation getting worse and finally leading to a major conflict, which means the destruction of all the values one holds”. (Nehru)

I hope that when historians look back at the seventieth anniversary of the United Nations, it will be remembered as a renaissance in global affairs rather than an episode of missed opportunity.

Thank you.

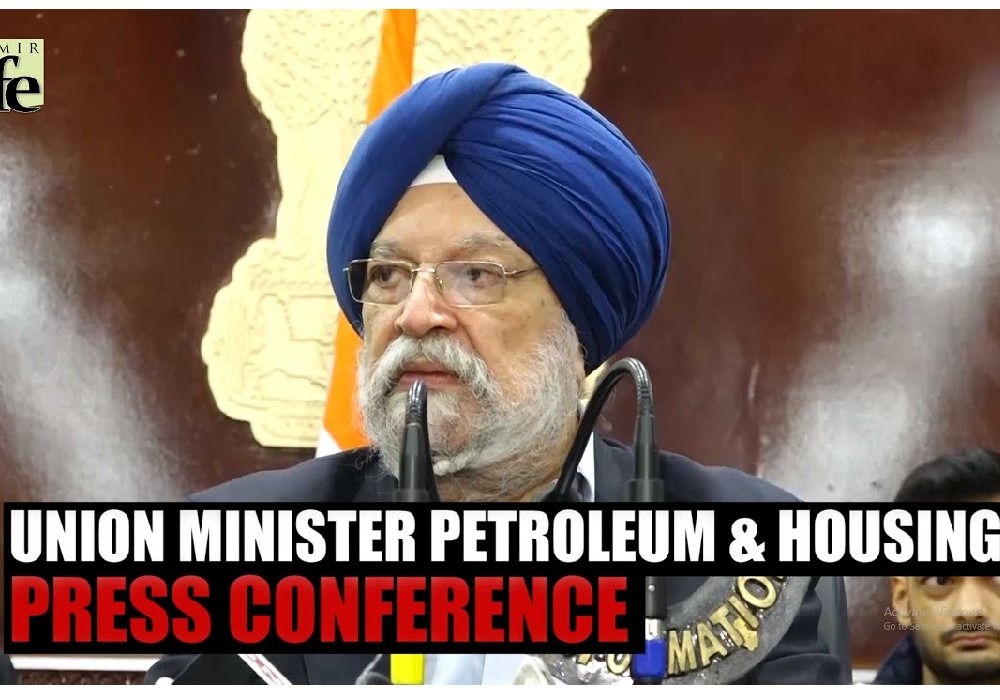

Synopsis Union Minister Hardeep Singh Puri stated India's commitment to an inclusive global energy future through open collaboration, highlighting the India-Middle ..

देश में एक करोड़ यात्री प्रतिदिन कर रहे हैं मेट्रो की सवारी: पुरी ..

Union Minister for Petroleum and Natural Gas and Housing and Urban Affairs, Hardeep Singh Puri addressing a press conference in ..

Joint Press Conference by Shri Hardeep Singh Puri & Dr Sudhanshu Trivedi at BJP HQ| LIVE | ISM MEDIA ..

(3).jpg)

"I wish a speedy recovery to former Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh Ji. God grant him good health," Puri wrote. ..